scarecrow interviews

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

Stewart Home Interview: Writing about writing...

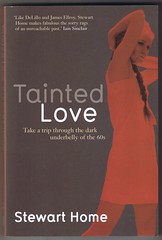

Stewart Home needs no introduction. A short preamble here wouldn’t do our subterranean behemoth enough justice. His latest novel Tainted Love has been labelled his most mainstream work of fiction yet. Stewart Home? Mainstream? Scarecrow’s editor Lee Rourke just couldn’t resist and had to investigate this straight from the man himself. Enjoy:

Picture courtesy of Andrew Gallix, 3am Magazine.

It is with great pleasure to introduce to you Mr Stewart Home:

Lee Rourke: Do you see Tainted Love as your most mainstream book to date?

Stewart Home: For a number of reasons this might be considered my most mainstream novel. I was interested in the ghosted autobiography as a literary form, and it’s a very mainstream phenomenon since it’s the rich and famous whose books are ghost-written, but I think I twist the genre considerably. For a start I’m quite upfront about the fact that what I’ve produced is a novel. Then, if you start thinking about what I’m doing, writing as if I’m my mother, then it’s coming from somewhere pretty weird. Also, my mother wasn’t really a mainstream person. She came to London from south Wales in 1960 at the age of sixteen and very shortly afterwards was hanging around at least three very distinct scenes. She was a club hostess in Soho working alongside Profumo scandal girl Christine Keeler, she was hanging out in the philosophy department in Gordon Square - where Stuart Hampshire had just taken over from A. J. Ayer as head, and while we might laugh at logical positivists these days, they were taken very seriously in the Anglo-American academic and media worlds back then – and my mother was heavily involved with the Notting Hill beatnik scene, and this entailed some pretty hardcore drug taking as a means of inner exploration. So although some of this stuff became mainstream, my mum was actually a hipster. One editor at a big publisher who really wanted to publish my work thought the book was some kind of joke, Stewart Home writes a commercial novel, and so he wouldn’t touch it. I presume he was worried about being made to look stupid, since he feared I might reveal I’d written a ‘mainstream’ book to hoax him. But this is the book I wanted to write and also the sections about R. D. Laing and the film-script in the middle of it are post-modern explorations of modernist experimentation. This constitutes about twenty thousand words of an eighty-thousand word book. So at most you might say the book appears three-quarters mainstream, but actually even this 75% is pretty whacked out when you start thinking about it. Tainted Love tells my mother’s story in a very thinly fictionalised form, and I dealt with her story in the way I thought was appropriate. I’m very proud of this book, and a lot of people have said they think it’s the best thing I’ve done.

Lee Rourke: Do you see Tainted Love as your most mainstream book to date?

Stewart Home: For a number of reasons this might be considered my most mainstream novel. I was interested in the ghosted autobiography as a literary form, and it’s a very mainstream phenomenon since it’s the rich and famous whose books are ghost-written, but I think I twist the genre considerably. For a start I’m quite upfront about the fact that what I’ve produced is a novel. Then, if you start thinking about what I’m doing, writing as if I’m my mother, then it’s coming from somewhere pretty weird. Also, my mother wasn’t really a mainstream person. She came to London from south Wales in 1960 at the age of sixteen and very shortly afterwards was hanging around at least three very distinct scenes. She was a club hostess in Soho working alongside Profumo scandal girl Christine Keeler, she was hanging out in the philosophy department in Gordon Square - where Stuart Hampshire had just taken over from A. J. Ayer as head, and while we might laugh at logical positivists these days, they were taken very seriously in the Anglo-American academic and media worlds back then – and my mother was heavily involved with the Notting Hill beatnik scene, and this entailed some pretty hardcore drug taking as a means of inner exploration. So although some of this stuff became mainstream, my mum was actually a hipster. One editor at a big publisher who really wanted to publish my work thought the book was some kind of joke, Stewart Home writes a commercial novel, and so he wouldn’t touch it. I presume he was worried about being made to look stupid, since he feared I might reveal I’d written a ‘mainstream’ book to hoax him. But this is the book I wanted to write and also the sections about R. D. Laing and the film-script in the middle of it are post-modern explorations of modernist experimentation. This constitutes about twenty thousand words of an eighty-thousand word book. So at most you might say the book appears three-quarters mainstream, but actually even this 75% is pretty whacked out when you start thinking about it. Tainted Love tells my mother’s story in a very thinly fictionalised form, and I dealt with her story in the way I thought was appropriate. I’m very proud of this book, and a lot of people have said they think it’s the best thing I’ve done.

You also have to remember that I don’t just do one style, I switch around and experiment, which confuses people in the trade because they’re used to authors who can’t or won’t write in more than one way. It’s definitely not commercial to change your style as radically as I do between different books. A lot of people who liked my early novels, all written in the third person and in a self-consciously pulp-splatter style, were very pissed off when I dropped the simulations of narratives in my fiction and published Come Before Christ & Murder Love. I’d always been interested in experimental writing, but the fact that Alain Robbe-Grillet, for example, had always been a big influence on me, wasn’t picked up by the critics until I did that book. But I was always, even in my earliest fiction, among other things, writing about writing. Perhaps not bizarrely, my most commercially successful novel prior to Tainted Love was 69 Things To Do With A Dead Princess, which on completely goes against the grain of the ‘mainstream’ sensibility. Dead Princess sells because people who grew on fifties and sixties experimental writing (a lot of whom weren’t born until the sixties and even seventies) aren’t at all well served by the publishing industry these days. That book also continues to sell well because it’s been picked up by people teaching English at universities. They teach Burroughs and Beckett and they’re really pleased to be able to set their students a contemporary book with lots of modernist tropes which have been twisted to reflect the way the culture has developed and atrophied. There is still a lot of interest in non-narrative literary explorations, but most publishers just won’t cater for it. Therefore if you can sneak a book into print that doesn’t patronise the reader, doesn’t assume they are thick, then despite the fact that according to the those running publishing houses it’s uncommercial, it is potentially an extremely commercial proposition if it’s well done – and Dead Princess is very well done – because there is absolutely no contemporary competition. But on the basis of the criteria used by the trade, Tainted Love is undoubtedly my most ‘mainstream’ book since Slow Death. Those two books and my first novel Pure Mania are generally judged to have the potential widest appeal by editors. But I don’t think too much about that sort of thing, I just write the books I want to write. Some are easier for the trade to deal with than others. I just do what I think is right for the book. I also like the challenge of trying new things.

LR: Is the sixties as a cultural influence over for us?

SH: It depends on what you mean by the sixties. The whole stoner culture which came out of the sixties, and which my mother was very much a part of, permeates everything these days, not just records but TV and cinema. But a lot of the more interesting literary and cinematic experimentation has been dumped. Most people’s idea of non-linear these days is more MTV than Last Year At Marienbad or Ann Quin. But people are increasingly bored with the blanding out of the culture that’s been going on for some time, there will be a resurgence, reinvention, redeployment and some completely unexpected new developments of all the best things about sixties modernism. It’s a matter of using elements of sixties culture to do something new, not simply replicating them. And it’s not really just the sixties we’re talking about. It’s about recognising we all have a stake in modernity, and moving on and off from that. So what really interests me is modernism as a whole, not just in its sixties guise, and in a lot of ways I’m most interesting in taking that up from where people like Rudy Ray More left off, fucking with the conventions and doing so with both attitude and humour. What we need to get away from is the obsession with cultural objects, so that we can put the focus back on the social relations within specific communities and between groups of people from which cultural forms emerge. The cultural industry will have to take this onboard eventually, because in its obsession with gaining the largest possible audience for a small number of cultural objects, it is ultimately on a hiding to nowhere. A book or whatever that is put together in the hope that it will appeal to everyone, ultimately appeals to no one. It misses the mark by aiming too wide. That’s what the current blanding out is all about, it entails removing all the elements that appeal to specific readers because these might be found difficult or offensive by someone else. People end up having best-sellers foisted on them rather than books they’d actually enjoy reading. It’s the mental equivalent of junk food. People don’t develop if they don’t read things that challenge them, that they disagree with, that they find disagreeable. You haven’t grown up until you’ve understood the value of reading a bad book, and the trade sells itself on enjoyment, on not offending. I read shitloads of books I dislike, and watch shitloads of films I think are shit, because I’m continuously educating myself. If you read something you disagree with, it can force you to develop and sharpen your positions, if you only read writers whose opinions you agree with then you’re not going anywhere.

LR: Do you see the writing/publishing of the memoir as a worthwhile literary form?

SH: I wrote Tainted Love precisely because I don’t find most memoirs worthwhile. They’re formulaic, particularly the celebrity memoir or autobiography. I wanted to create the double of the memoir, something with a twist and that recorded a genuinely interesting life. Celebrities are never interesting, they’ve become pure image with all their humanity removed from them, celebrities are just an abstraction of what it is to be human and their pseudo-lives aren’t of interest to me at all. I’m more interested in people who can’t afford to do rehab in The Priory, but unfortunately it’s the rich and famous who most usually get their memoirs published. Not all memoirs are bad, and since we’re dealing with the sixties I might as well mention some examples which address that era. I thought Brian Barritt’s autobiography The Road Of Excess was very interesting as far as it went. The problem with the book is that because Barritt wants to be perceived as a psychedelic warrior, he doesn’t really detail his involvement in a whole range of drug dealing, and knowing about this makes a bit more sense of his life. Barritt only really touches on stuff like pot and LSD which are acceptable to weekend hippies, although he does at least mention his smack use. He’s also very funny on Alex Trocchi, so the book is well worth reading despite a few reservations. I also liked parts of Hammond Guthrie’s AsEverWas: Memoirs of a Beat Survivor. He’s very good on the early psychedelic scene in California, some great stuff about the scene there, I’m not so interested in his juvenile pranks or the breakdown of his marriage, but he writes well.

LR: As most of your fiction is an anti-narrative, is Tainted Love an anti-memoir?

SH: It’s definitely an anti-memoir, and it’s more truthful than most memoirs because it presents itself as an anti-novel, as fiction. Probably more of the book is literally true than most people would imagine, but it wasn’t possible to tell the whole story because the guilty must be protected, in part because of the ridiculously stringent libel laws in the UK. One day, perhaps, the whole story can come out. But that said, my novel is a far better approximation of ‘truth’ than any ghost-written ‘autobiography’ that presents itself as ‘non-fiction’.

LR: Patti Smith is ostensibly an influence. Discuss.

SH: I was telling someone the other day that I acquired Patti Smith’s first album Horses when I was fourteen, and the woman I was talking to said that was very early, and I replied that the album came out in 1975, the year before, so it wasn’t that early. I always thought Patti Smith was hilarious, like all her shit about. It was so pretentious, in the literal meaning of the term, that I just loved it. Patti Smith was speaking in tongues, and she didn’t seem to know what the fuck she was singing about. But the spirit was great. I loved "Gloria" and "Land" on that first album. The sound was perfect, but she sure as hell wasn’t hip, like she could have gone for Villon, or someone, but no Patti opts for absolutely the most obvious romantic poetic cliché in the form of Rimbaud. If she’d been less pretentious, if she’d actually known what the fuck she was talking about, she wouldn’t have been as good. I loved "Piss Factory" and her version of "Hey Joe", but when I was a teenager back in the late seventies for me the best thing she’d done was the live version of The Who’s My Generation. I’d just crack up every time I heard her scream ‘John Cale bass guitar solo’ and you’d get about two notes. At that time I also got hold of the Nuggets double compilation album put together by her guitarist Lenny Kaye, and that was a revelation, all those groovy garage punk classics from the sixties by The Electric Prunes and The Seeds, I loved that stuff when I was teenage. As soon as The Pebbles albums started coming out, I got those too, from Pebbles 1 onwards. The sixties seemed so long ago to me then, like it was the stone-age, although those garage punk recordings were only a decade old. Back then, those recordings felt to me to be a lot older than stuff that came out in the late-seventies sounds to my ears now. Even the sixties sounds like yesterday now, whereas when I was fourteen or fifteen I thought stuff from 1966 sounded positively antediluvian.

LR: Are there any writers you admire who you feel do not get the attention they deserve?

SH: There are lots, and among contemporary writers I think Lynne Tillman stands out in particular as someone who really ought to be much more widely read than she is at present. Her new novel American Genius is coming out on Soft Skull, I’m really looking forward to reading that. My favourite Tillman book is Cast In Doubt, which is about a gay writer called Horace and his obsession with a girl whose disappeared called Helen. On a meta-level Horace represents classicism or modernism, and Helen stands for romanticism or post-modernism. So the book is all about Horace’s quest for Helen and his inability to find her, and the complete meaninglessness of her diary to him when he acquires that. But Lynne has done a lot of really good books. Anything by her is worth reading, fiction or non-fiction. To take just one more writer, an older one this time, I really like Clarence Cooper Junior, who Canongate republished in their Payback series of classic black writing about ten years ago, but I think he’s out of print in the UK. No doubt you can pick him up used or on import. A lot of people think Cooper’s last novel The Farm is his best. It’s about being forced to clean up from heroin addiction as a con, and his sexual and other obsessions that accompany this, the minutiae and inhumanity of prison life etc. It’s fairly autobiographical but Cooper presents it as a novel. The Farm is a stunning piece of writing, but I also really like his earlier books too.

LR: What next? Are there any more novels on the way?

SH: In terms of writing, I have a novel I wrote before Tainted Love that still isn’t published called "Memphis Underground". There was an independent publisher interested in that, but it contains four basic strands and the editor I was dealt with only liked three of them, so he wanted me to remove the final strand and replace it with something else. I didn’t want to do that, so this novel will come out when I find a publisher who likes all of what I’ve done with it. The first half "Memphis Underground" uses that classic sci-fi device of cutting two narratives together which turn out to be the same person’s life six months apart, so in the second of the cut narratives he’s taken on another identity. It’s about all sorts of things but other than using this sci-fi trope, it isn’t science fiction. I’ve got another novel I’ve done called "Mandy, Charlie & Mary-Jane", which is about a drug-addled college lecturer who turns into a serial killer. I want to do some revisions on that, but it’s written in draft form. I’ve also done a non-fiction biography of my mother, but I’m not ready to publish that yet because of potential legal problems. So that will have to sit in a draw until certain people have died, it could come out in two years time, or it might have to wait twenty-years before there’s any chance of it being published. Sometime within the next year I’m also planning to start work on a new novel called "Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie", it will be set in the contemporary art world. However, I’m also learning ventriloquism. I just got a £8800 grant from the Live Art Development Agency, which enables me to take time out to learn some new skills. I’m exited about the prospect of presenting readings from my fiction wrapped into a ventriloquist act. That’s what’s really keeping me busy right now. I love ventriloquist dummies, they’re such an archetypal symbol of modernism…

LR: Stewart, welcome to scarecrow, and thanks for your time…

For further information please visit The Stewart Home Society.